Indexing and Slicing#

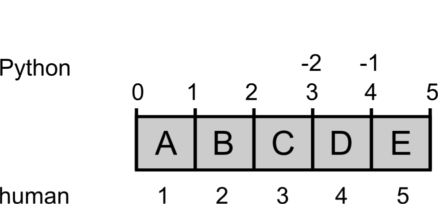

Computers and people count differently:

Computers treat an address in memory as the starting point of a body of data. In the same sense, an index in Python always refers to such a starting point, something that is in between two objects in memory. We humans in contrast always count the objects themselves.

This is why the indices used to slice lists are a bit unintuitive at first, e.g. in:

s = "my fat cat"

s[3:6]

'fat'

'fat'

'fat'

The diagram provides a practical model by which you can deduce indices yourself.

Indexing#

Many data types (lists, strings) allow to index items by their position:

s = 'my fat cat'

s[0] # first

'm'

s[2] # third

' '

s[-1] # last

't'

Using and index that does not exist causes an IndexError.

Slicing#

We can define intervals. This is called slicing:

s = 'my fat cat'

s

'my fat cat'

s[3:6] # -> 'fat'

'fat'

Slices may be open on either side:

s[3:] # -> 'fat cat'

'fat cat'

s[:6] # -> 'my fat'

'my fat'

If you leave both number out, you copy the variable. This is sometimes a neat trick, if you want to manipulate a list, but preserve the original.

d = [1, 2, 3]

d

[1, 2, 3]

e = d[:]

e

[1, 2, 3]

d.append(4)

d

[1, 2, 3, 4]

len(d) # is now 4

4

len(e) # still 3

3

You can define slices with a step size:

s = 'my fat cat'

s

'my fat cat'

s[1:8:2] # -> 'yftc'

'yftc'

s[:8:2] # -> 'm a '

'm a '

s[1::2] # -> 'yftct'

'yftct'

The step size may even be negative:

s = 'my fat cat'

s

'my fat cat'

s[::-1] # -> 'tac taf ym'

'tac taf ym'